The Effects of Bodyworn Cameras Bwcs on Police and Citizen Outcomes a Stateoftheart Review

Abstract

Objectives

To assess the furnishings of BWCs on prosecutorial and courtroom-related charge outcomes across multiple crime types, including domestic violence charges, crimes committed against constabulary officers, and drug/alcohol charges.

Methods

A cluster-randomized controlled trial with 22 spatiotemporal constabulary units assigned to BWCs and 17 assigned to command conditions. Data from the State Attorney's Role were used to rails convictions, adjudication withheld dispositions, and declined prosecutions for both experimental and control charges. A series of multilevel logistic and negative binomial regression models were used to judge the event of BWC footage on charge outcomes.

Outcomes

BWCs led to a significantly college proportion of crimes against police officers resulting in convictions or arbitrament withheld outcomes, and a significantly higher proportion of domestic violence charges resulting in convictions alone, compared to command charges. Nevertheless, after the clustering effect was taken into account, just the effect of BWCs on crimes confronting police officers remained statistically meaning.

Conclusion

These early results suggest that BWCs accept significant evidentiary value that varies by criminal offence type. BWCs may be best suited to capture prove of crimes committed against law officers and potentially in domestic violence offenses as well.

Introduction

Largely prompted by highly publicized police shootings in the United states, torso-worn cameras (BWC) accept become 1 of "the well-nigh apace diffusing and costly technologies recently adopted past policing agencies" (Lum et al., 2020, p. 3). Police enforcement agencies around the globe take increasingly turned to BWCs to increase perceptions of accountability and transparency (Coudert et al., 2015; Hyland, 2018; Taylor, 2016), and billions of dollars in revenue take been, and keep to be, spent on BWC implementation (Friedman, 2015; Goodison et al., 2018). In response, research on the effects of BWCs has increased significantly in recent years. Yet, such enquiry has primarily concentrated on a small set of outcomes, with item focus on the effect of BWCs on utilise-of-force incidents and citizen complaints (meet Ariel et al., 2015; Ariel et al., 2017; Jennings et al., 2015; Lum et al., 2019; Lum et al., 2020; Maskaly et al., 2017; White & Malm, 2020).

As researchers continue to focus on the impacts of BWCs on constabulary-citizen encounters, incomparably less attention has been given to the evidentiary value of BWC footage (see Lum et al., 2019). Through video capture of the behavior, statements, and/or demeanor of suspects and victims, BWCs may produce evidence that leads to improved case processing and outcomes for both victims and offenders (meet Fan, 2017; Goodall, 2007; White, 2014). Stated differently, BWCs have the potential to both "implicate and exonerate" (White et al., 2019, p. 9), and yet despite this potential, few studies take examined the effect of BWCs on the prosecution and courts (see Lum et al., 2019; see more than recently Williams et al., 2021), with fifty-fifty fewer published experimental assessments. Given that US Land courts handle upwards of 15 one thousand thousand criminal cases each year (Court Statistics Projection, 2020) and the adoption of BWCs continues to abound, understanding the impact of BWC footage on case outcomes is increasingly important. The current study adds to this limited trunk of research by analyzing court outcomes across various criminal offence types following a 6-month cluster-randomized trial of BWCs in Miami Beach, Florida (inside 12 months later the completion of the experiment).

Background

The potential for BWCs to provide evidence for case processing has been cited past researchers and practitioners since the early on stages of the BWC movement (come across Goodall, 2007; Merola et al., 2016; White, 2014). To engagement, yet, research on the impacts of BWCs on court-related outcomes has been express and inconclusive. Using experimental and quasi-experimental designs, respectively, Owens et al. (2014) and Morrow et al. (2016) found that domestic violence incidents attended by officers wearing BWCs were associated with increased criminal justice outcomes such as charges filed, prosecutions, plea agreements, and guilty verdicts, relative to comparison cases (meet also Ellis et al., 2015). In a modest-scale pilot study, Goodall (2007) noted increases in the proportion of criminal incidents leading to arrest post-obit BWC implementation, and ODS Consulting (2011) found that criminal cases in a BWC airplane pilot jurisdiction were more than probable to be disposed of via early guilty plea when BWC video was used.

Nonetheless, several methodologically rigorous studies have failed to find any upshot of BWCs on court outcomes. Tracking the dispositions of misdemeanor drug and alcohol cases following a randomized controlled trial (RCT) in Tempe (AZ), White et al. (2019) noted no pregnant differences in guilty outcomes betwixt BWC cases and control cases. Similarly, Yokum et al. (2017) found no significant differences in charges prosecuted, guilty pleas, or guilty verdicts between aggregate BWC cases and control cases following a RCT implemented with the Washington (DC) Metropolitan Police Department. All the same, Yokum et al. were unable to analyze incidents where the initial charge was amended by prosecutors. Additionally, Ariel et al. (2019) take noted spillover concerns when causal inferences are fabricated from tests that suffer from treatment contamination or situations in which BWC officers are present at control incidents.

Ane potential caption for these inconsistent results is that the effect of BWC video on court outcomes varies significantly past criminal offence blazon. In domestic violence cases, for instance, BWC footage might amend capture victim statements and visible injury (Morrow et al., 2016; Westera & Powell, 2017), while in drug/alcohol cases, such footage might better capture the actions and demeanor of the suspect (see Groff et al., 2018; White et al., 2019), when compared to written reports or officer testimony solitary. Other types of cases, such as crimes committed against constabulary officers (i.e., assail and/or battery of an officeholder, resisting abort, etc.), may besides benefit from the presence of BWCs, peculiarly if these offenses occur in direct view of the photographic camera and thus provide an opportunity for the criminal offence to be captured on video. Indeed, both qualitative and quantitative evidence suggests that the likelihood that prosecutors volition view BWC video prior to charging decisions varies by offense type, with domestic violence, drug/alcohol, and bombardment of police officer/resisting arrest charges among the nearly frequently viewed offense categories (see Groff et al., 2018). To appointment, still, there has been no intra-jurisdictional comparing of court outcomes across these law-breaking types, making information technology difficult to make up one's mind whether the inconsistency seen in prior inquiry is influenced past crime blazon. Furthermore, existing studies have not however assessed the impact of BWCs on the prosecution of crimes committed confronting police officers.

Our objective in this study was to examine whether BWCs affect the likelihood that a criminal charge will result in various forms of guilty outcomes, formal convictions, and declined prosecutions. The data (North = 2,605) come from a 6-month randomized controlled trial implemented in partnership with the Miami Beach Police force Department (MBPD) and the Bureau of Justice Assistance'due south Smart Policing Initiative (SPI) programme conducted from January to June 2017. Given that prior BWC experiments take suffered from issues related to treatment contamination, such that treatment and command officers often respond to the aforementioned incidents (see Ariel et al., 2019), the current study attempts to limit this possibility by employing a cluster-randomized design in which discrete spatiotemporal units (i.e., geographic and temporal shifts) were randomly assigned to treatment (BWC) and command (no BWC) conditions. A partnership with the State Attorney's Office provided unique access to court processing information on experimental and control offenses. Our inferences and outcomes were concentrated at both the cluster and accuse level, with specific focus on domestic violence charges, drug/booze charges, and crimes committed confronting police officers (east.g., assault or battery of a police force officeholder, resisting abort) as these cases are most likely to exist affected by the presence of a camera. To our cognition, this is the first test of the impact of BWCs on courtroom outcomes beyond multiple crime types within the same jurisdiction. By comparing these outcomes within the same setting, we hope to provide stronger inferences regarding the potential for BWC bear witness to vary in utility beyond criminal offense types. Results of these analyses may have of import implications for BWC policy at both the police and prosecutorial level.

Written report site

Miami Embankment spans an surface area of 7.63 foursquare miles on the east declension of Florida. During 2017 (the year of the report period), Miami Embankment had a residential population of approximately 91,000 people and was the 26th largest city in Florida. Footnote ane The residential population is over 50% Hispanic and 30% White, with a median income of roughly $54,000, and a 14% poverty charge per unit (US Census Bureau, 2021a; US Census Agency, 2021b). Crime in Miami Embankment is traditionally driven by an affluence of tourism, nightlife, and subsequent drug use/distribution, with over 8,000 alphabetize crimes per 100,000 population in 2019 (run across Florida Department of Constabulary Enforcement, 2019; Kurtz et al., 2009). The city is separated into four main team areas corresponding to the northward, fundamental, southward, and entertainment districts of the metropolis. The north district encompasses the northernmost section of the city between 63rd street and 87th terrace. This expanse is mostly residential with a higher poverty charge per unit than the residuum of the city. The middle commune extends from approximately 17th to 63rd street and is considered a wealthier residential surface area. The south district stretches from between 16th and 17th street in the northward to the southern tip of the peninsula. This expanse contains virtually of the bars, clubs, and nightlife that the metropolis is known for. Appropriately, the entertainment district lies within the due south district, representing an area approximately two blocks wide and extending from 16th street in the north to 5th street in the due south (Askew, 2021).

Experimental blueprint

Xxx-ix police spatiotemporal units were randomly assigned to either treatment (BWCs) or control (no BWCs) conditions for a 6-month intervention menstruation lasting from Jan i, 2017, to June 11, 2017. Unlike previous experiments that accept used police shifts (Ariel et al., 2015; Ariel et al., 2020), officers (Yokum et al., 2017), or spatial hotspots (Ariel, 2016), here we used a combination of fourth dimension and infinite and officers. That is, geographic team areas (N = 10) were combined with both specific shifts and specific days to form spatiotemporal units that were then randomly assigned to treatment or control. Thus, handling and command units operated within the same geographic areas but did not operate simultaneously. Those assigned to the same surface area were assigned on different days or times, while those assigned during the same days and times were assigned to different areas. All general patrol locations/units were included in the study, with the exception of some specialty units (e.g., gang suppression, hole-and-corner, canine unit). Included team areas comprised the s, centre, north, and entertainment sectors of the city, in addition to several smaller patrol beats within these areas. The day and shift components of the experiment involved sets of three successive days (due east.chiliad., Fri, Sabbatum, Sunday; Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday; Tuesday, Wednesday, Th) and separate shift assignments (day, afternoon, and midnights shifts). A full randomization tabular array tin be establish in the Supplementary Materials.

At the moment of random assignment, the location, solar day, and shift were inseparable, representing a 3-way interaction. This interaction was natural to the MBPD's normal course of operations. Every 6 months, the MBPD shuffles the assignment of police force officers into area/day/shift combinations in a process colloquially referred to as the "shift bid." Some officers stay in the same cluster over time while others rotate; yet, the spatiotemporal units remain consequent throughout the 6-month period. Thus, during the experimental period, these units were mutually exclusive, such that no officer assigned to a BWC condition was too assigned to a command condition. Officers were required to be in their assigned geographic areas on the assigned days and times each calendar week for the entirety of the intervention menses.

In line with Campbell and Stanley's (1963; see too Ariel et al., 2022) recommendations, cluster randomization was chosen every bit to avert treatment contamination and violation of the stable unit handling value supposition (SUTVA) that may occur when BWC officers and control officers respond to the same incident (run into Ariel et al., 2019; Rosenbaum, 2007). In other words, past randomly assigning BWCs to all police officers operating within the same geographic expanse, on the same days, and for the aforementioned shift, the potential for interaction between handling and command groups should exist limited. The population of spatiotemporal units in Miami Embankment averaged roughly v officers (M = 5.13) and 1,066 calls for service (One thousand = 1,065.74) per cluster (Supplementary Materials).

Randomization of team surface area/day/shift combinations was conducted with a simple random assignment generator, such that each unit had an equal gamble of receiving treatment or control. This procedure resulted in 22 experimental clusters and 17 command clusters, with all officers in the experimental clusters being assigned BWCs and no officers in control clusters being assigned BWCs. BWCs were positioned on officers' uniforms, and officers had no discretion about when and how to use the BWCs, with a coating policy of activation in all police-public engagements. Officers were instructed to activate their BWCs at the commencement of each telephone call and to then categorize the call later completion. At the end of each shift, officers and so uploaded whatsoever video that they captured when docking their BWC.

Treatment weather were near common on Mondays, Tuesdays, and Wednesdays (24% of experimental units), while command conditions were nigh mutual on Sundays, Mondays, and Tuesdays (29% of control units). Additionally, experimental shifts were almost usually day shifts (38% of shifts), and command shifts were most commonly afternoon shifts (35% of shifts); however, there were no significant dependencies between experimental condition and twenty-four hours of the week (χ2(6) = 3.80, p = 0.seventy) or shift consignment (χ2(iii) = 3.67, p = 0.95). Experimental and control groups also experienced similar levels of calls for service (CFS), with twenty,949 full CFS in clusters with BWC assignment and 20,615 CFS in clusters without BWC assignment. However, squad areas without BWC assignment did experience higher average CFS (M = ane,212.65; SD = 594.46) than squad areas with BWC consignment (G = 952.23; SD = 673.94) over the course of the study. The baseline comparability of the treatment and control clusters is shown in Table 1.

Study population and eligibility criteria

The study population consisted of arrests initiated by police officers (proactively or reactively) and and so sent to the local Florida prosecutor's office for review. Given our involvement in assessing the evidentiary impact of BWCs on individual accuse-level outcomes, with "charge" referring to an individual arrest/allegation, eligible clusters were required to have produced at least one criminal accuse that was sent to the State Chaser's Office for prosecution and was disposed of during our follow-up period. This resulted in the exclusion of ane experimental cluster which produced no prosecuted cases with recorded dispositions, leaving 38 remaining clusters available for assay (21 treatments and 17 controls). Footnote two

Individual charge data were provided by the Land Attorney'southward Office, who prosecutes all cases in Miami-Dade County, in partnership with the MBPD. This immune united states of america to capture information on incidents that occurred during the study catamenia. Due to the small overall population size of clusters, cluster sample sizes were unequal, and in total, there were 2,779 (M = 73.13; SD = 71.19 per cluster) charges that occurred beyond the 38 clusters, with ane,568 (Chiliad = 74.66; SD =74.61 per cluster) charges associated with BWC footage and i,211 (M = 71.24; SD = 68.96 per cluster) charges non associated with BWC footage.

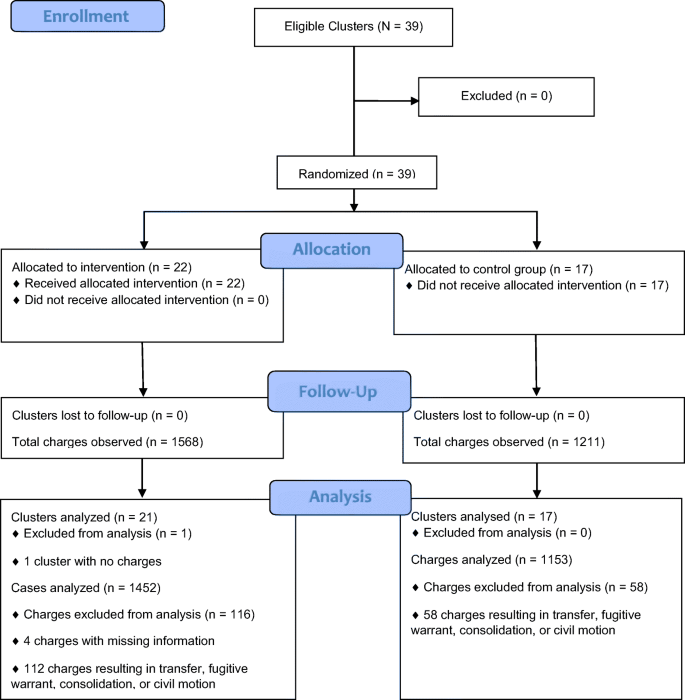

For charges to be considered eligible for assay, however, nosotros required information on the arrest or filing charge description, the cluster that the incident originated from, whether the incident was attended by an officeholder wearing a BWC, and the concluding charge disposition. This led to the exclusion of 174 charges that were either missing arrest or filing information, were transferred to some other court, resulted in a fugitive warrant, became consolidated with other cases, or resulted in a civil motion. Thus, there were one,452 (M = 69.fourteen; SD = 69.53 per cluster) BWC charges considered valid for assay and 1,153 (Thousand = 67.82; SD = 65.40 per cluster) command charges considered valid for analysis, resulting in a total valid sample size of two,605 charges (Grand = 68.55; SD = 66.81 per cluster). Within this final sample, 54% of charges in experimental clusters were classified as misdemeanors, 44% were classified as felonies, and 2% were juvenile offenses. This did not significantly differ from control clusters, where 52% of charges were classified equally misdemeanors, 46% were classified as felonies, and 2% were juvenile offenses (χ2(2) = 2.01, p = 0.37). Footnote 3 The Espoused diagram in Effigy 1 provides a detailed overview of the allocation, inclusion, follow-up, and assay stages useful for understanding the flow of charges and the rationale for excluding sure observations. Footnote 4

Consort diagram for BWC cluster and case

Dependent and independent variables

Several court-related effect measures were employed to examine the evidentiary value of BWCs. Of primary importance is the causal inference between the presence of BWC footage at the charge-level and various guilty and not guilty outcomes. However, equally separate outcomes, nosotros also isolated formal convictions and charges that the State Attorney's Office declined to prosecute, which are probable to contain a separate set of causal mechanisms that touch decision-making processes.

Convictions + arbitrament withheld

Nosotros chose to aggregate convictions and adjudication withheld outcomes to represent the total sample of charges that involved enough show to find the defendant guilty. "Adjudication withheld" (Chiricos et al., 2007, p. 547) is a disposition in which evidence is deemed sufficient for a finding of guilt but where a formal conviction is deferred, oftentimes to provide the accused with an opportunity to complete some court-imposed mandate such every bit probation (Hayes-Smith & Hayes-Smith, 2009; Spohn et al., 1998). Convictions, however, include the formal finding of guilt through any ways (e.g., jury trials, bench trials, and plea bargains). Footnote 5 It is important to annotation that these outcomes are unique and accept meaningful differences which should not be ignored. Given our focus on the potential for BWCs to produce evidence, still, the combination of these measures was intended to increment statistical ability while even so isolating cases in which bear witness was deemed sufficient for a finding of guilty. Footnote 6

This aggregate measure was operationalized as a dichotomous variable (1/0) contrasted against the outcomes of all other prosecutions that did not result in a guilty disposition, which included acquittals, dismissals, and charges that were nolle prossed (charges dropped past the prosecution). Footnote 7 In total, 55.2% (n = 433) of charges with sufficient bear witness for a finding of guilt were classified equally adjudication withheld, and approximately 95% (due north = 1,075) of the remaining charges were nolle prossed.

Convictions

Given that the label of a formal conviction often creates a host of consequences related to voting, employment, and housing rights (see Hoskins, 2018), we also separated convictions from adjudication withheld outcomes as an boosted sub-analysis. Thus, convictions are a subset of our combined measure. In this case, nevertheless, they represent a dichotomous variable that is assorted confronting the outcomes of all other prosecuted charges rather than acquittals, dismissals, and nolle pros outcomes lone. In other words, we were interested in whether BWC charges were more or less likely to event in formal convictions as opposed to any other event (including adjudication withheld) one time the State Attorney's Office decided to prosecute, so we could gauge the upshot of BWC footage in such cases.

No activeness cases

Our information contained information on incidents where no action was taken by the State Attorney's Office. These are arrests in which prosecution was declined, and given prior inquiry suggesting that BWC footage may be an important predictor of prosecutors' filing decisions (see Groff et al., 2018), these charges were analyzed separately as a detached result (i.due east., charges filed vs. not filed).

Operationalization of crime blazon

Outcome measures were examined for the full sample of charges, as well as separately for domestic violence charges, drug/booze charges, and crimes against police officers, given the stronger theoretical potential for BWC footage to exist salient for these offenses. While domestic violence incidents could be identified directly, drug/alcohol charges and crimes against police force officers are composite measures combining multiple accuse descriptions. Drug/booze charges include various forms of intoxication, possession, and distribution/manufacturing, while crimes against police officers include assault and/or battery of a police force enforcement officer and multiple forms of resisting abort. In total, approximately 80% (n = 719) of drug/alcohol charges involved possession of drugs, and approximately 82% (n = 272) of crimes committed against police officers were classified every bit resisting abort.

Presence of BWC

The contained variable of interest is whether the criminal incident/arrest sent to the State Attorney's Part for review was initiated by a responding officeholder who was wearing a BWC. More than specifically, this is a mensurate of whether the incident occurred in a location and time where all patrol officers were assigned BWCs. It is possible that treatment incidents could accept spilled over into command areas (or vice versa); however, a allegiance check indicated that all incidents considered valid for analysis were initiated by officers in the correct experimental condition. In full, all experimental incidents were owing to 84% (n = 87) of BWC officers, and all control incidents were owing to 76% (north = 74) of command officers.

Arrests in this context could be also considered either proactive or reactive. That is, an arrest could have been made during or shortly afterward a call took identify, or alternatively, at a later signal in time if there was a delay in reporting or an investigation was needed. Naturally, the more time that elapses between an incident and a constabulary response, the less opportunity BWCs may have to capture textile evidence of the criminal offence. In total, approximately 96% of aggregate arrests, 95% of domestic violence arrests, 99% of drug/booze arrests, and 98% of arrests for crimes committed against police officers occurred on the same appointment as the offense. Additionally, the majority (53%) of eligible BWC charges began as officer initiated CFS. Taken together these results suggest that officers were in shut spatial and temporal proximity to the offenses represented in our analyses.

Despite this, information technology should be noted that our independent variable is not a directly measure of whether a BWC produced meaningful evidence or whether the resulting footage was formally or informally used past the Country Attorney'southward Function during filing decisions, criminal hearings, trials, plea negotiations, or other judicial processes (addressing this question requires a critical review of the footage itself, which was exterior the scope of this study, and would provide data on the treatment arm of the experiment only). Across the total sample, 55.7% (northward = 1,452) of charges were initiated past an officer wearing a BWC, and 44.3% (n = 1,153) of charges were not. Bivariate frequencies and cross tabulations between our dependent and independent variables can be seen in Table 2.

Statistical methods

Nosotros get-go examined whether there were statistically meaning differences in the bivariate frequencies for each issue mensurate between BWC charges and control charges (Table 2). Multilevel logistic regression analyses were and so used to estimate the effect of BWC video on charge outcomes while accounting for the cluster-level variance (i.e., the variance attributable to the spatiotemporal unit of measurement). Footnote 8 Earlier estimating these models, nosotros conducted likelihood ratio tests to confirm that there was meaning variation in court outcomes across experimental clusters. To do so, nosotros compared the log-likelihood of our unconditional multilevel models to those of standard logistic regression models containing no covariates. Footnote 9 Our independent variable representing the presence/absence of a BWC was and so added to these models as a fixed outcome, while squad surface area remained as a random upshot (varying intercept). The final specification of our multilevel models is represented by the following two-level equation (run across Johnson, 2010):

$$ {\eta}_{ij}={\beta}_{0j}+{\beta}_1{BWC}_{ij} $$

$$ {\beta}_{0j}={\gamma}_{00}+{\mu}_{0j} $$

Here η ij represents the log odds of a given court upshot, β 0j is the intercept for each team surface area/day/shift combination (which is our unit of measurement of assignment), and β 1 represents the fixed effect regression coefficient for BWCs. At the second level of the equation, the cluster-level intercepts (β 0j ) are comprised of both the overall intercept across clusters (γ 00) and the random variance of the intercepts for each cluster (μ 0j ). This model became our primary belittling approach; however, due to the low overall incidence of domestic violence convictions, we analyzed this event using a negative binomial regression model. Footnote 10 In other words, for this outcome, we compared the count of domestic violence convictions between experimental and control surface area/24-hour interval/shift combinations. As such, this effect was analyzed at the cluster level, and therefore, the results pertain only to the clusters as opposed to the individual charges. All analyses were conducted in R statistical software, with multilevel models estimated using the lme4 (Bates et al., 2015) and lmerTest packages (Kuznetsova et al., 2017).

For logistic regression models, odds ratios were used equally measures of result size (see Chen et al., 2010), and the intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC) were calculated using the latent variable arroyo (come across Snijders & Bosker, 2012), which uses the variance estimate of the standard logistic regression model as the level 1 error term. For the negative binomial regression model (domestic violence convictions), the consequence size is represented by the incident charge per unit ratio (meet Wilson, 2021). While the unit of measurement of assay in this model is the cluster, an ICC value was calculated using the method described by Tseloni and Pease (2003), which divides the random furnishings variance of an unconditional mixed model past the sum of this variance and the dispersion parameter. Every bit nosotros noted, our cluster sample sizes varied across crime types and statistical tests, as not all clusters produced cases corresponding to each crime type. While there is debate surrounding the number of clusters needed to produce unbiased estimates in a multilevel model, research has suggested that this technique tin can exist used with as few as 10 groups (see Bong et al., 2014; Raudenbush & Bryk, 2002), fewer than the minimum number of clusters we included in a single analysis (n = 24).

Results

In total, 30.1% (n = 784) of charges resulted in conviction or adjudication withheld outcomes, while 43.v% (n = i,132) of charges resulted in acquittal, dismissal, or nolle pros, and 26.four% (n = 689) of charges were declined prosecution. Additionally, only 13.5% (n = 351) of the total sample of charges resulted in a formal criminal conviction. As tin be seen in Table ii, when a BWC was present (every bit opposed to not present), a significantly higher proportion of domestic violence charges resulted in a conviction (xiv.vi% vs. 2.1%, p = .047), even though the base charge per unit for convictions in both treatment and control groups was very low.

Crimes committed against police officers wearing BWCs also experienced a significantly higher proportion of combined conviction and adjudication withheld outcomes than crimes committed against control officers (44.one% vs. 29.8%, p = .014). Nevertheless, crimes committed against officers wearing BWCs likewise resulted in no action dispositions (i.e., declined prosecution) in a significantly higher proportion of cases than crimes committed confronting control officers (26.3% vs. sixteen.8%, p = .041).

No other significant bivariate differences were establish, though drug/booze charges attended past control officers resulted in conviction or arbitrament withheld outcomes at a notably higher rate than drug/booze charges attended past BWC officers, based on a .10 significance threshold (45.ix% vs. 39%, p = .078).

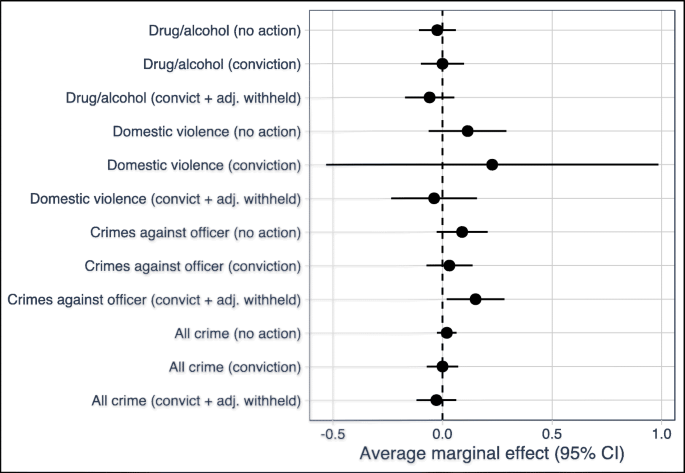

Table three displays the consequence estimates based on our multilevel logistic and negative binomial regression models. No significant effects of BWC presence were constitute beyond aggregate crime measures, domestic violence measures, or drug/booze measures. Yet, after accounting for the cluster-level variance, crimes confronting police officers were significantly more likely to issue in confidence or adjudication withheld outcomes when a BWC was nowadays (β = 0.66, p = 0.029, OR = one.93, 95% CI [1.09, 3.76]). Specifically, when prosecuted by the State Chaser'due south Office, the odds of a confidence or adjudication withheld upshot were 93% greater for charges in which a BWC was present than for charges in which a BWC was not present. Footnote 11

When because the clustering effects, withal, domestic violence convictions and no action outcomes for crimes against police officers practice not retain the significant relationships seen in the bivariate assay. Of note, all domestic violence convictions in which a BWC was present occurred within the same experimental cluster. Likely as a result of this, and the small domestic violence sample size, the ICC values for domestic violence convictions and combined confidence and arbitrament withheld outcomes are very large. Given that almost all of the full variance in these outcomes can be attributed to the betwixt-cluster variance, we are unable to suggest with confidence that there is an effect of BWC footage on the outcomes of these charges.

Figure 2 further illustrates these findings by plotting the average marginal effects from our regression models. Though domestic violence convictions announced to experience the largest effect, the confidence intervals for this prediction are considerable. In contrast, the probability of a confidence or arbitrament withheld upshot for crimes against law officers remains positive and does not overlap with the no-upshot line, indicating that the presence of a camera in these cases significantly increases the probability of this combined outcome measure.

Marginal effects of BWCs on court outcomes

Discussion and limitations

Following a half-dozen-month cluster-randomized trial in Miami Beach (FLA), this study uses 12 months of follow-upward data provided by the Country Attorney's Office to examine the effect of BWCs on court outcomes across various types of criminal charges in a single jurisdiction. Our results suggest that, for the prosecution of crimes against police officers (assault/battery of an officer, resisting arrest), BWCs led to a 93% increase in the odds of a confidence or adjudication withheld outcome relative to control charges. Such a finding is probable not unexpected, every bit BWCs are in a unique position to capture the characteristics of the law-breaking in these situations given that these crimes are committed against the photographic camera wearer. However, this finding is interesting given that many BWC proponents envisioned this applied science leading to an increased likelihood of successful prosecution for crimes committed by police officers rather than crimes committed against police officers (see Mateescu et al., 2016; Smith, 2019). While we are unable to identify any specific prosecutions of law officers in our data, time to come studies should examine these cases and dissimilarity them with the prosecution of crimes committed confronting police officers.

Regarding crimes committed against law officers, nosotros also annotation mixed prove of a college proportion of BWC cases being declined prosecution. Such a finding, when taken in light of the significantly greater odds of combined convictions and adjudication withheld outcomes for these charges, would seem to be consequent with the suggestion that BWCs can pb to fewer only stronger prosecutions (see Groff et al., 2018; Grossmith et al., 2015; White et al., 2019). If true, this would suggest that BWCs have the ability to provide objective testify that is beneficial to all parties involved in a criminal instance. However, circumspection is urged when interpreting this effect, given that it did non remain significant after adjusting for the variance in declined prosecutions at the cluster level.

Our findings concerning the result of BWCs on domestic violence charges should also be considered promising notwithstanding not definitive. There was a significantly higher bivariate proportion of domestic violence charges in which a BWC was present that resulted in a conviction, relative to control charges. Even so, the sample sizes were minor, and we could not separate the bear on of the BWCs from the impact of the spatiotemporal unit for this outcome. The bivariate analyses offering insight that suggests a strong treatment effect for domestic violence charges that are otherwise difficult to prosecute (Westera & Powell, 2017). On the other paw, we lacked sufficient statistical ability to place this effect, given the limited base rates (Hinkle et al., 2013). More than research on these outcomes is needed, particularly with larger sample sizes and rigorous methodologies.

Additionally, we failed to place a significant touch on of BWCs on the outcomes of drug/alcohol charges. Such offenses often crave police officers to identify subjective signs of intoxication (see White et al., 2019) or may even involve allegations of fabricated bear witness (see Fan, 2017), thus providing theoretical rationale to believe that BWCs would show useful during prosecution. Nevertheless, our statistically nonsignificant findings for these charges are consistent with those of White et al. (2019). It is perhaps possible that BWCs can provide evidence of intoxication but not provide evidence of drug/alcohol possession, or vice versa. One hypothesis may be that intoxicated suspects are more likely to confront officers, every bit alcohol is linked to an intensified perception of self-righteousness and imitation accusation of police officers' wrongdoing (Denton & Krebs, 1990); however, nosotros find no bear witness for this merits. While suspects may become more argumentative while intoxicated, BWCs practise not seem to affect these circumstances 1 fashion or another, and we were unable to make these distinctions in our information. Future analyses should attempt to decide if the effects of BWCs differ based on these more specified situations.

Additional caveats deserve attention in future research. First, we are unable to show if and how BWC footage was viewed and used by prosecutors nor practise nosotros have an in-depth understanding of the means in which constabulary investigators employ BWC content to support the case confronting defendants. While prior inquiry suggests that, in the majority of cases where a accuse is filed, BWC footage will be viewed at some point during instance processing (Groff et al., 2018), the specific mechanisms that lead to these observed furnishings are presently unknown. Hereafter enquiry in this area would benefit from measures of viewing and usage rates, as well as information regarding when and how BWC footage is used throughout the court process, particularly beyond various offense types (e.one thousand., how BWC footage is actively used during plea negotiations, case grooming, trials, motions to suppress, etc. and how this may vary by law-breaking type.). Time to come RCTs conducted in collaboration with local prosecutor's offices should strive to capture some of these measures to explore mediating factors within a randomized controlled framework. This may allow researchers to examine what happens in-between BWC assignment and the downstream effects that they observe.

Despite this limitation, however, it is frequently necessary to first institute that an intervention may have a true outcome in guild to provide a ground for more specific analyses on the mechanisms backside that consequence. While we are unable to speak directly to what transpired between the random assignment of BWCs and the effects that nosotros observed, our methodological approach allows us to reasonably infer that the observed outcome was set in motion by the BWC consignment (see discussion in Weisburd, 2003). Additionally, sensitivity analyses (run into footnote 11) supported our main findings while holding constant a number of demographic and case-level variables ofttimes thought to influence court outcomes. Nonetheless, this "blackness box" (Famega et al., 2017, p. 106) issue is non uncommon in experimental criminology, where information technology is ofttimes not possible to explicate the factors that mediate the relationship between a handling and an effect (Green et al., 2010).

In addition, some outcomes were not statistically significant at the usual statistical thresholds once the clustering result was taken into account. As noted, this presents a statistical ability consideration; even so, nothing findings for several outcome measures (but non in others) do not necessarily indicate a lack of effect. For case, given that BWC footage may benefit both the prosecution and defence force, it is possible that these effects cancel each other out in the aggregate. The discussion should then be nigh targeting areas of law enforcement in which the intervention is the well-nigh likely to accept the strongest desirable outcome. While we are shortly unable to examine these possibilities, future research should explore these underlying causal mechanisms to determine with more specificity the settings in which BWC footage impacts, or fails to impact, court outcomes. Such inquiry may benefit from being conducted at a more individual level, perhaps using example studies or court observations to examine how oft (and the ways in which) BWCs benefit both the prosecution and the defense.

A related limitation is that we are currently unable to distinguish betwixt outcomes achieved via plea understanding and those achieved via trial verdict. While it has been well documented that plea bargains business relationship for over 95% of all convictions in state and federal courts (Bureau of Justice Statistics, 2010, 2015), the impact of BWCs on particular adjudicatory methods remains an of import area for future enquiry. Qualitative interviews with legal actors advise that BWC footage may not just increase plea negotiations at early on processing stages (Todak et al., 2018), but may besides play an of import role in cases that do progress to trial (run across Gaub et al., 2020). Thus, we encourage future research to explore the upshot of BWC prove on both the frequency of sure adjudicatory processes and the outcomes of these processes with as much specificity equally possible. However, doing so may also require extended follow-upwards periods. Our sample of charges represents only those that reached disposition during a 12-month post-intervention period, and nosotros are currently unable to determine how many charges were still pending or whether the outcomes of these charges would differ from those in our sample. Follow-up periods of multiple years may exist needed, particularly given the lengthy nature of case processing.

Finally, it is possible that the clusters of officers and the incidents they responded to in our study differ from those that are typical in other areas, every bit Miami Beach is dissimilar many other constabulary jurisdictions (given its uber-active nighttime economic system and big transient population during holiday seasons). Given that our study took place in a single city with limited sample sizes for several consequence measures, more than research of this nature is needed.

Conclusions

Despite these limitations, the results of this study are non without important theoretical and policy implications. The nonsignificant human relationship between BWCs and amass case outcomes coupled with the pregnant (albeit limited) effects plant in the crime blazon analyses suggests that the utility of BWC show is nuanced. In other words, the effect of BWC footage on case outcomes may indeed be dependent on the nature of the crime. From a theoretical perspective, this is just logical, as crimes that are frequently characterized past delayed discovery or reporting (due east.g., residential holding theft or burglary) are unlikely to benefit from the unique ability of BWCs to record events as they unfold or in their immediate aftermath.

From a policy perspective, however, the implications are that both police and prosecutors may exist able to improve employ BWC footage if they are focused on the specific situations in which footage is likely to exist useful. Many have expressed business organization with the increased workload and time commitment that BWCs place on legal actors (run across Gaub et al., 2020; Groff et al., 2018; Merola et al., 2016; Todak et al., 2018). Understanding the event of BWC footage on court outcomes with greater specificity given to crime types and adjudicatory processes may allow police to make more informed decisions when tagging evidence and allow prosecutors to prioritize cases when reviewing video. Equally the specificity of these findings increases, potential policy options regarding video capture, tagging, and viewing can go increasingly evidence based. Ultimately, such findings may assistance jurisdictions to amend manage large amounts of BWC footage while still using them to meliorate criminal justice outcomes.

Our strongest conclusion should therefore be that equipping frontline officers with BWCs may cause variations in some criminal justice system outcomes, compared to a policy of not equipping frontline officers with BWCs. Nevertheless, the evidentiary effects of BWCs appear to differ by offense type, and future inquiry is needed to exam the generalizability of this claim and the mechanisms behind it. Ultimately, only through understanding these furnishings can the adoption and implementation of BWCs be meliorate informed at a jurisdictional level.

Notes

-

Due to the consistent influx of tourism, all the same, the true population of Miami Beach at any given time far exceeds that of the residential population.

-

The spatiotemporal unit that was excluded consisted of a twenty-four hour period shift on Saturdays, Sundays, and Mondays inside a smaller, lower crime, surface area of the city that was patrolled by merely ane officer.

-

While our analyses were focused on the charge-level rather than the defendant or case-level, randomization appeared to be constructive in equating the experimental and command groups on a number of factors known to influence courtroom outcomes. The boilerplate number of charges per instance was 1.67 (SD = 1.35) in command clusters and 1.67 (SD = one.fifteen) in experimental clusters, t(1560) = 0.09, p = 0.93. The average age of defendants in each instance was 32.57 years (SD = eleven.69) in command clusters and 32.95 years (SD = 11.32) in experimental clusters, t(1560) = −0.65, p = 0.52. Additionally, 85.3% of the charges in command clusters were associated with male person defendants and 87.1% of charges in experimental clusters were associated with male defendants, χ2(1) = 1.45, p = 0.23. Information technology should be noted, however, that there was a significantly college proportion of charges associated with Black defendants in experimental clusters than control clusters (52.8% vs. 48.5%), χ2(1) = 4.69, p = 0.03.

-

Nosotros were often unable to identify the adjudicatory method through which charges were tending of within the data and cannot say what proportion of convictions or adjudication withheld outcomes were reached via plea agreement, bench trial, jury trial, etc.

-

As an illustrative example, we conducted sensitivity ability analyses for independent proportions using G*Power 3 (encounter Faul et al., 2007). Results suggested that to maintain a power level of 0.viii across all outcomes with an alpha level of 0.05 and a two-tailed examination, the necessary effect sizes ranged from h = 0.13 to h = 0.65 for convictions solitary, h = 0.13 to h = 0.62 for arbitrament withheld outcomes alone, and h = 0.13 to h = 0.61 for adjudication withheld outcomes and convictions combined. Thus, combining these measures allowed for slight reductions in the effect sizes necessary to place treatment effects while remaining theoretically consistent with the purposes of our study.

-

Charges in which no action was taken by prosecutors were not included in this variable and were instead treated equally a distinct issue.

-

Logistic regression models with cluster robust standard errors were besides estimated. At that place were no substantive differences betwixt the results of the multilevel models and the models with robust standard errors.

-

In that location were iv outcomes that did not demonstrate significant variance across clusters. These outcomes were convictions or adjudication withheld outcomes for crimes against officers (χ2 = 0.88, p = 0.347), convictions for crimes against officers (χii = 0.081, p = 0.776), no action outcomes for domestic violence charges (χ2 = 0.054, p = 0.816), and no action outcomes for drug/alcohol cases (χtwo = 3.17, p = 0.075). Yet, we still chose to report the results for these outcomes using multilevel models, both to remain consistent with the design of the experiment and to increment reporting homogeneity beyond outcomes. Additionally, standard logistic regression models were estimated for these outcomes and indicated no substantive differences from our multilevel models.

-

A likelihood ratio test for overdispersion indicated that a negative binomial model should be used by rejecting the null hypothesis that the Poisson model was non overdispersed (χii = 24.29, df = i, p < .001).

-

In footnote 3 we cited bear witness of a significant bivariate departure in the racial composition of BWC and non-BWC defendants. As a sensitivity analysis, nosotros added race (Blackness/White/Other) as a covariate to the model predicting confidence or adjudication withheld outcomes for crimes against law officers. BWCs remained a meaning predictor of conviction or adjudication withheld outcomes in this model (OR = one.95, 95% CI [i.07, 3.55], p = 0.03). Additionally, results remained statistically significant when controlling for the race and age of the defendant, as well as the severity of the current charge (misdemeanor/felony) and the total number of charges in each instance (OR = 2.04, 95% CI [1.07, 3.89], p = 0.03).

References

-

Ariel, B. (2016). Increasing cooperation with the law using body worn cameras. Police Quarterly, 19(3), 326–362. https://doi.org/10.1177/1098611116653723.

-

Ariel, B., Farrar, Due west. A., & Sutherland, A. (2015). The effect of constabulary body-worn cameras on use of force and citizens' complaints confronting the police: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Quantitative Criminology, 31(3), 509–535. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10940-014-9236-3.

-

Ariel, B., Sutherland, A., Henstock, D., Young, J., Drover, P., Sykes, J., et al. (2017). "Contagious accountability" a global multisite randomized controlled trial on the upshot of police trunk-worn cameras on citizens' complaints against the police. Criminal Justice and Beliefs, 44(two), 293–316. https://doi.org/ten.1177/0093854816668218.

-

Ariel, B., Sutherland, A., & Sherman, L. Due west. (2019). Preventing handling spillover contamination in criminological field experiments: The case of torso-worn police cameras. Journal of Experimental Criminology, fifteen(iv), 569–591.

-

Ariel, B., Mitchell, R. J., Tankebe, J., Firpo, Thousand. E., Fraiman, R., & Hyatt, J. One thousand. (2020). Using habiliment technology to increment constabulary legitimacy in Uruguay: the case of trunk-worn cameras. Law & Social Inquiry, 45(1), 52–80. https://doi.org/x.1017/lsi.2019.13.

-

Ariel, B., Bland, Thousand. P., & Sutherland, A. (2022). Experimental Designs. SAGE Publications.

-

Askew, S. (2021). Key components of mayor'south plan to overhaul Miami Beach's amusement district canonical. RE Miami Beach. https://www.remiamibeach.com/southward-beach/key-components-of-mayors-plan-to-overhaul-miami-beachs-entertainment-district-approved/

-

Bates, D., Maechler, G., Bolker, B., & Walker, Southward. (2015). Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. Periodical of Statistical Software, 67(1), 1–48. https://doi.org/ten.18637/jss.v067.i01.

-

Bell, B. A., Morgan, G. B., Schoeneberger, J. A., Kromrey, J. D., & Ferron, J. K. (2014). How low can you go? Methodology, ten, 1–xi. https://doi.org/10.1027/1614-2241/a000062.

-

Bureau of Justice Statistics. (2010). Felony defendants in big urban counties, 2006 - statistical tables. United states of america Department of Justice.

-

Bureau of Justice Statistics. (2015). Federal justice statistics, 2012 - statistical tables (NCJ Written report No. 248470). Washington D.C.: U.S. Section of Justice.

-

Campbell, D. T., & Stanley, J. C. (1963). Experimental and quasi-experimental designs for inquiry on instruction. In N. L. Gage (Ed.), Handbook of enquiry on didactics (pp. 171–246). Rand McNally.

-

Chen, H., Cohen, P., & Chen, South. (2010). How big is a large odds ratio? Interpreting the magnitudes of odds ratios in epidemiological studies. Communications in Statistics - Simulation and Ciphering, 39(iv), 860–864. https://doi/org/10.1080/03610911003650383

-

Chiricos, T., Barrick, Thousand., Bales, W., & Bontrager, S. (2007). The labeling of bedevilled felons and its consequences for backsliding. Criminology, 45(3), 547–581. https://doi.org/x.1111/j.1745-9125.2007.00089.x.

-

ODS Consulting (2011). Body worn video projects in Paisley and Aberdeen, self- evaluation. Retrieved from bwvsg.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/07/BWV-Scottish-Study.pdf

-

Coudert, F., Butin, D., & Le Métayer, D. (2015). Body-worn cameras for police accountability: Opportunities and risks. Estimator Law and Security Review, 31(6), 749–762.

-

Courtroom Statistics Project (2020). Country court caseload digest: 2018 information. National Eye for State Courts. Retrieved from http://www.courtstatistics.org/__data/assets/pdf_file/0014/40820/2018-Digest.pdf.

-

Denton, K., & Krebs, D. (1990). From the scene to the crime: The issue of alcohol and social context on moral judgment. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 59(ii), 242.

-

Ellis, T., Jenkins, C., & Smith, P. (2015). Evaluation of the introduction of personal issue torso worn video cameras (Operation Hyperion) on the Island of Wight: Last study to Hampshire constabulary. Portsmouth, England: Institute of Criminal Justice Studies, University of Portsmouth. Retrieved from port.air-conditioning.great britain/media/contacts-and-departments/icjs/downloads/Ellis-Evaluation-Worn-Cameras.pdf

-

Famega, C., Hinkle, J. C., & Weisburd, D. (2017). Why getting inside the "blackness box" is important: Examining treatment implementation and outputs in policing experiments. Police Quarterly, 20(1), 106–132. https://doi.org/10.1177/1098611116664336.

-

Fan, K. D. (2017). Justice visualized: Courts and the body photographic camera revolution. UCDL Review, fifty, 897.

-

Faul, F., Erdfelder, Eastward., Lang, A. G., & Buchner, A. (2007). Grand* Power three: A flexible statistical power assay program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Beliefs Research Methods, 39(ii), 175–191. https://doi.org/x.3758/BF03193146.

-

Florida Department of Law Enforcement (2019). Canton and municipal law-breaking report. Retrieved from https://www.fdle.state.fl.united states of america/FSAC/UCR/2019/County_and_Municipal_Offense_Report_2019A.aspx

-

Friedman, U. (2015). Do police force body cameras actually work? The Atlantic. Retrieved from: http://world wide web.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2014/12/exercise-police-trunk-cameraswork-ferguson/383323/

-

Gaub, J. Eastward., Naoroz, C., & Malm, A. (2020). Constabulary BWCs as 'neutral observers': Perceptions of public defenders. Policing: A Periodical of Policy and Practice. https://doi.org/10.1093/police/paaa067.

-

Goodall, Grand. (2007). Guidance for the police use of trunk-worn video devices: Police force and crime standards directorate. London, U.K.: Home Office. Retrieved from library.college.constabulary.united kingdom of great britain and northern ireland/docs/homeoffice/guidance-trunk-worn-devices.pdf.

-

Goodison, S., Davis, R., & Wilson, T. (2018). Costs and benefits of body-worn camera deployment. Washington D.C.: Police force Executive Research Forum. Retrieved from https://www.policeforum.org/avails/BWCCostBenefit.pdf

-

Greenish, D. P., Ha, South. E., & Bullock, J. G. (2010). Enough already about "black box" experiments: Studying arbitration is more difficult than most scholars suppose. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 628(1), 200–208. https://doi.org/ten.1177/0002716209351526.

-

Groff, Due east. R., Ward, J. T., & Wartell, J. (2018). The function of torso-worn camera footage in the conclusion to file. Study for the Laura and John Arnold Foundation. Philadelphia, PA: Criminal Justice Department, Temple University.

-

Grossmith, L., Owens, C., Finn, W., Mann, D., Davies, T., & Baika, L. (2015). Police, photographic camera, evidence: London'southward cluster randomised controlled trial of trunk worn video. College of Policing.

-

Hayes-Smith, J., & Hayes-Smith, R. (2009). Race, racial context, and withholding adjudication in drug cases: A multilevel examination of juvenile justice. Journal of Ethnicity in Criminal Justice, 7(3), 163–185. https://doi.org/ten.1080/15377930903140300.

-

Hinkle, J. C., Weisburd, D., Famega, C., & Ready, J. (2013). The problem is not just sample size: The consequences of low base of operations rates in policing experiments in smaller cities. Evaluation Review, 37(3-four), 213–238.

-

Hoskins, Z. (2018). Criminalization and the collateral consequences of conviction. Criminal Law and Philosophy, 12(4), 625–639. https://doi.org/x.1007/s11572-017-9449-2.

-

Hyland, South. South. (2018). Body-worn cameras in law enforcement agencies, 2016. Washington, DC. U.S. Department of Justice, Part of Justice Programs, Bureau of Justice Statistics.

-

Jennings, Westward. G., Lynch, One thousand. D., & Fridell, L. A. (2015). Evaluating the bear on of police officer body-worn cameras (BWCs) on response-to-resistance and serious external complaints: Evidence from the Orlando law department (OPD) experience utilizing a randomized controlled experiment. Journal of Criminal Justice, 43(6), 480–486. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrimjus.2015.10.003.

-

Johnson, B. D. (2010). Multilevel assay in the written report of offense and justice. In A. R. Piquero & D. Weisburd (Eds.), Handbook of quantitative criminology (pp. 615–648). Springer.

-

Kurtz, S. P., Inciardi, J. A., & Pujals, E. (2009). Criminal activity among young adults in the social club scene. Police force Enforcement Executive Forum, 9(2), 47–59.

-

Kuznetsova, A., Brockhoff, P. B., & Christensen, R. H. B. (2017). lmerTest package: Tests in linear mixed effects models. Journal of Statistical Software, 82(13), 1–26. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v082.i13.

-

Lum, C., Stoltz, M., Koper, C. S., & Scherer, J. A. (2019). Research on body-worn cameras: What we know, what we need to know. Criminology & Public Policy, xviii(1), 93–118. https://doi.org/x.1111/1745-9133.12412.

-

Lum, C., Koper, C. S., Wilson, D. B., Stoltz, M., Goodier, G., Eggins, Eastward., et al. (2020). Torso-worn cameras' effects on police officers and denizen behavior: A systematic review. Campbell Systematic Reviews, 16(three), e1112. https://doi.org/ten.1002/cl2.1112.

-

Maskaly, J., Donner, C., Jennings, Westward. Grand., Ariel, B., & Sutherland, A. (2017). The effects of body-worn cameras (BWCs) on police and citizen outcomes: A state-of-the-art review. Policing: An International Journal of Law Strategies & Management, xl, 672–688. https://doi.org/ten.1108/PIJPSM-03-2017-0032.

-

Mateescu, A., Rosenblat, A., & boyd, d. (2016). Dreams of accountability, guaranteed surveillance: The promises and costs of trunk-worn cameras. Surveillance and Society, 14(1), 122–127.

-

Merola, Fifty. Yard., Lum, C., Koper, C. S., & Scherer, A. (2016). Trunk worn cameras and the courts: A national survey of state prosecutors. Report for the Laura and John Arnold Foundation. Fairfax, VA: Center for Show-Based Law-breaking Policy, George Bricklayer University.

-

Morrow, W. J., Katz, C. M., & Choate, D. Due east. (2016). Assessing the impact of police body-worn cameras on arresting, prosecuting, and convicting suspects of intimate partner violence. Law Quarterly, nineteen(3), 303–325. https://doi.org/ten.1177/1098611116652850.

-

Owens, C., Isle of man, D., & Mckenna, R. (2014). The Essex body worn video trial: The touch of torso worn video on criminal justice outcomes of domestic abuse incidents. Ryton-on-Dunsmore, Coventry, England: Higher of Policing. Retrieved from bwvsg.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/07/BWV_ReportEssTrial.pdf

-

Raudenbush, S., & Bryk, A. (2002). Hierarchical linear models: Applications and data analysis methods (2d ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

-

Rosenbaum, P. R. (2007). Interference between units in randomized experiments. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 102(477), 191–200. https://doi.org/10.1198/016214506000001112.

-

Smith, Yard. (2019). Policing: What changed (and didn't) since Michael Brownish died? The New York Times. Retrieved from https://world wide web.nytimes.com/2019/08/07/u.s./racism-ferguson.html

-

Snijders T. A. B., Bosker R. (2012). Multilevel analysis. M Oaks, CA: Sage.

-

Spohn, C., DeLone, Chiliad., & Spears, J. (1998). Race/ethnicity, gender and judgement severity in Dade County, Florida: An examination of the conclusion to withhold adjudication. Journal of Crime and Justice, 21(2), 111–138. https://doi.org/x.1080/0735648X.1998.9721603.

-

Taylor, Due east. (2016). Lights, camera, redaction… police trunk-worn cameras; autonomy, discretion and accountability. Surveillance and Society, xiv(ane), 128–132.

-

Todak, N., Gaub, J. E., & White, M. D. (2018). The importance of external stakeholders for law body-worn photographic camera diffusion. Policing, 41(4), 448–464. https://doi.org/10.1108/PIJPSM-08-2017-0091.

-

Tseloni, A., & Pease, K. (2003). Repeat personal victimization. 'Boosts' or 'flags'? The British Journal of Criminology, 43(ane), 196–212. https://doi.org/x.1093/bjc/43.1.196.

-

U.s.a. Census Agency (2021a). City and town population totals: 2010-2019. [Tabular array]. Retrieved from https://www.census.gov/data/tables/fourth dimension-series/demo/popest/2010s-total-cities-and-towns.html

-

United States Census Agency (2021b). Quickfacts – Miami Embankment urban center, Florida [Table]. Retrieved from https://world wide web.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/tabular array/miamibeachcityflorida/POP010210

-

Weisburd, D. (2003). Ethical practise and evaluation of interventions in criminal offense and justice: The moral imperative for randomized trials. Evaluation Review, 27(iii), 336–354. https://doi.org/10.1177/0193841X03027003007.

-

Westera, N. J., & Powell, Grand. B. (2017). Prosecutors' perceptions of how to amend the quality of evidence in domestic violence cases. Policing and Lodge, 27(ii), 157–172. https://doi.org/10.1080/10439463.2015.1039002.

-

White, Grand. D. (2014). Constabulary torso-worn cameras: Assessing the testify, .

-

White, Grand. D., & Malm, A. (2020). Cops, cameras, and crisis: The potential and the perils of police force body-worn cameras. NYU Press.

-

White, Thousand. D., Gaub, J. E., Malm, A., & Padilla, K. E. (2019). Implicate or exonerate? The impact of police trunk-worn cameras on the adjudication of drug and booze cases. Policing: A Periodical of Policy and Practice. https://doi.org/10.1093/law/paz043

-

Williams, M., Weil, N., Rasich, E., Ludwig, J., Chang, H., & Egrari, S. (2021). Body-Worn Cameras in Policing: Benefits and Costs. NBER Working Paper No. w28622, Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3814611

-

Wilson, D. B. (2021). The relative incident rate ratio effect size for count-based touch on evaluations: When an odds ratio is not an odds ratio. Journal of Quantitative Criminology. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10940-021-09494-w.

-

Yokum, D., Ravishankar, A., & Coppock, A. (2017). Evaluating the furnishings of police force body-worn cameras: A randomized controlled trial. The Lab @ DC. Retrieved from bwc.thelab.dc.gov/TheLabDC_MPD_BWC_Working_Paper_10.20.17.pdf.

Funding

This project was supported by the Bureau of Justice Assistance's Smart Policing Initiative program under Grant #2015-WY-BX-002.

Author information

Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open up Access This commodity is licensed under a Artistic Commons Attribution iv.0 International License, which permits utilise, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as yous give appropriate credit to the original author(southward) and the source, provide a link to the Artistic Commons licence, and betoken if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Artistic Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the textile. If fabric is not included in the commodity's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is non permitted past statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted apply, yous volition need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

Reprints and Permissions

Nearly this article

Cite this commodity

Petersen, K., Mouro, A., Papy, D. et al. Seeing is assertive: the impact of body-worn cameras on courtroom outcomes, a cluster-randomized controlled trial in Miami Beach. J Exp Criminol (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11292-021-09479-vi

-

Accepted:

-

Published:

-

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s11292-021-09479-six

Keywords

- Body-worn camera

- Police force

- Prosecution

- Adjudication withheld

- Confidence

- Criminal justice

Source: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11292-021-09479-6

Post a Comment for "The Effects of Bodyworn Cameras Bwcs on Police and Citizen Outcomes a Stateoftheart Review"